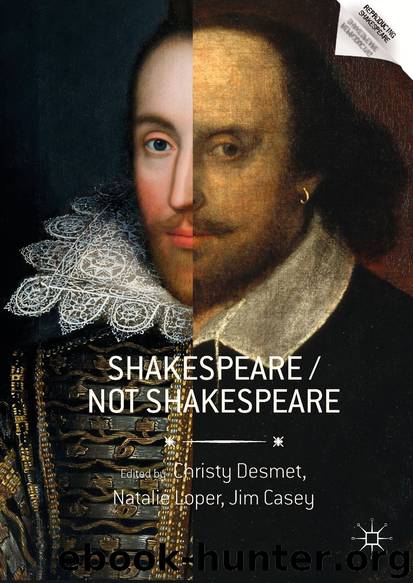

Shakespeare Not Shakespeare by Christy Desmet Natalie Loper & Jim Casey

Author:Christy Desmet, Natalie Loper & Jim Casey

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Springer International Publishing, Cham

I

The way in which the splash page of O’Neil’s story plays with notions of authorship and influence, bringing together characters and themes from multiple authors, is enabled, in part, by the particular nature of comics authorship. Due to a number of interrelated factors, including the historically fraught relationship between publishers and creators regarding intellectual property and credit, not to mention compensation, and the impermanent association of creators with particular comics series—especially mainstream, mass-market comics series—authorship in comics has perhaps been a more fluid concept than it is usually understood to be in other creative fields. 4 This has given rise to an intense investment, by both fans and creators (many of whom came to the comics industry by way of fandom), in tracing the work and influence of particular writers and artists. Within the industry, creators have often crafted their work as homage (both ironic and not) to earlier comics creators and eras. This backward-looking tendency, unsurprising in an industry built in large part on reworking the same stories, themes, and characters for decades, has had the effect of establishing a canon of recognizable gestures and styles, of creating a hierarchy of influences whose signs were deployed for the benefit of a subset of readers who could be counted on to recognize and decode them.

Much of this signaling work, as Daniel Stein argues, is done within the comics’ paratextual apparatus. As Genette notes in Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, “text is rarely presented in an unadorned state, unreinforced and unaccompanied by a certain number of verbal or other productions, such as an author’s name, a title, a preface, illustrations” (1). These other “productions,” which Genette names the text’s “paratexts,” are “what [enable] a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and, more generally, to the public” (1). Citing Philippe Lejeune’s Le Pacte Autobiographique (1975), Genette describes paratextual apparatuses as “a fringe of the printed text which in reality controls one’s whole reading of the text” (2). In comics , one of the key effects of these paratextual contextualizations is the working out of questions of influence and authority. Daniel Stein argues that, within the comics’ paratexts, “the notion of comic book authorship solidifies, and author fictions begin to take center stage” (162). Within these paratextual spaces, writers, artists, and publishers create for readers an authorial context within which to read a particular comic. Fighting against popular conceptions of comics as “formula stories told by anonymous insignificant authors” (Stein 161), comics’ paratexts assert cultural and literary authority by repeatedly drawing attention to connections between comics and canonical literature. By bringing Shakespeare and his works into the paratextual apparatuses of their comics, creators and publishers align their texts with Shakespeare-as-Author, framing their works (and their work) as partaking in a tradition of authorship not as corporate (in both senses), but in what is commonly referred to as the Romantic tradition and conception of authorship as an individual, “originary” act (Woodmansee and Jaszi 3). 5 Shakespeare functions

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Classical | Arthurian Romance |

| Beat Generation | Feminist |

| Gothic & Romantic | LGBT |

| Medieval | Modern |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

| Renaissance | Shakespeare |

| Surrealism | Victorian |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12354)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7730)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7302)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5741)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5726)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5392)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5066)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4920)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4706)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4552)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4534)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4500)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4425)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4080)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4010)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3990)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3979)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3961)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3828)